Food, Drugs, and the Family Secret

Posted by estiator at 11 November, at 11 : 28 AM Print

Confronting substance abuse in our community, at work and at home.

By Michael Troumbakis

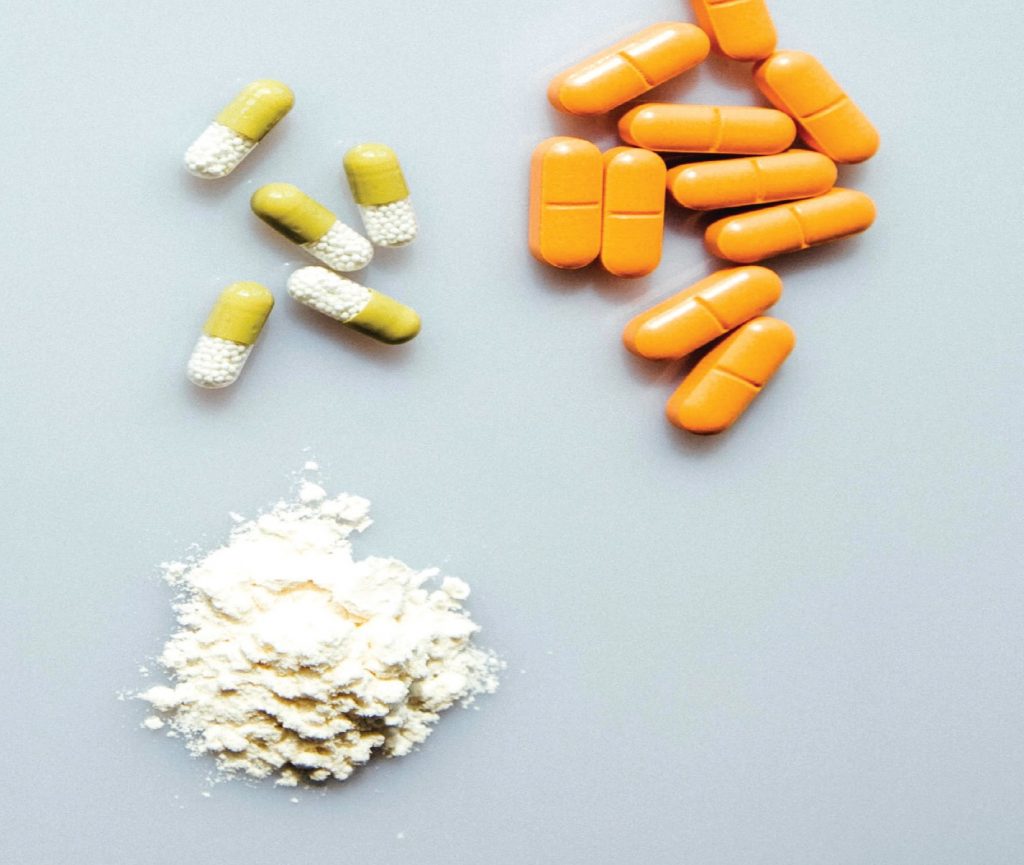

In 2003, legendary Greek singer Vicky Moscholiou shocked the Greek world by revealing she had cancer. (She succumbed to the illness two years later.) The shock came not because she had cancer, but because she revealed it publicly. Speaking openly about health matters is something that doesn’t come easily in the Greek culture. And while her public admission has helped others open up about their health struggles, there continues to be both a silence and a stigma in the global Greek community when it comes to such matters—including, to a significant extent, the Greek-American community in the United States. That silence and that stigma are even more pronounced when the health issue has to do with addiction. It’s well-documented that the restaurant industry, in which so many Greek-Americans toil, is rife with alcohol and drug abuse. In fact, according to experts, restaurant workers have the highest incidence of alcoholism and the third-highest drug abuse rate among all professions. Across the generations, Greek-Americans have shown that they are not immune to the perils of addiction. The following vignettes, then, are recounted here not to exploit or sensationalize, but to draw attention to the problems that few discuss openly. In each case the names have been changed along with some details, but the stories are real, and they serve as a cautionary tale.

When Stelios was born, it was five years after the birth of his middle sister, and seven years after the birth of his older sister. Coming from a very traditional Greek family, it was no surprise that he quickly became the family’s golden child. While his sisters were judged at every turn (what they wore to school, who they went to prom with, how well they spoke Greek, what sort of grades they turned in), Stelios was given a free pass to do as he pleased. And where the girls were pressured to find husbands as soon as they finished college, Stelios, on the other hand, was discouraged from settling down too soon. When he finally settled down, no one squeaked when it was with a non-Greek, even after his middle sister was estranged for bringing a “xeno” into the family. As is the case with many sons born to Greek parents, Stelios could do no wrong, even though he barely made it through college, and even though the woman he married came with bad habits: namely, partaking in occasional recreational drug use. Stelios’s early days of married life were a breeze. His father had set him up with a restaurant all his own about 40 minutes from the city where he was born and raised. Fast cash brought fast friends. And soon Stelios began falling into the trap of partying every night when the restaurant closed. At first it was nothing out of the ordinary—drinks, occasionally marijuana. But as the partying continued, it became more intense, with cocaine making it into the mix. Within a couple of years, it wasn’t just after work, but throughout the day. And before the end of his third year in business, Stelios was a full-fledged addict, and his business was slipping through his fingers. By his fifth year of marriage, his wife left him, and the business was shuttered. And it wasn’t until this time that the family accepted there was a substance abuse problem, although they refused to accept the idea that Stelios was a drug

addict. He was drinking too much, they rationalized. With the business closed up and his wife out of the picture, they tried to bring him home, but it took another year to get him back. And when he finally did come back, the secret was out. When they finally stopped being in denial, nearly a decade had passed and Stelios’s life was in complete tatters while they struggled to keep him sober. Rehab didn’t come into the picture until a few years of unsuccessful efforts by the family to tackle his problems without professional help. Today, after a couple of costly stays in rehab, Stelios is healthy but bitter, blaming his sisters (one of whom became a successful restaurateur in her own right) for robbing him of an inheritance that he squandered. And those closest to him know that he is just one drink away from falling back into the downward spiral of addiction and misery.

Sakis was the only child of Leo and Despina. Leo, who came to the United States in his early 20s, was a larger-than-life figure in his community. A first-class reveler, he was a fixture in the bouzouki joints, where he would spend thousands of dollars in a night. Seldom sober, Leo led the life of a celebrity, fed by a steady stream of cash that he generated from his busy diner. From the time that Sakis was born, his parents nurtured him into the role of Leo’s heir—both as a business owner and as a lady’s man and the life of the party. By the time he was 13, he was drinking to intoxication, with his parents’ blessing, as well as smoking cigarettes and losing his virginity in a house of ill repute. When he was 16, he was a fixture at the Greek nightclubs and sleeping with women 10 years his senior. He was discouraged from going to college and knew nothing except that which he learned from his father’s business.

As he got older and began to socialize outside of his father’s orbit, Sakis took up with friends that got him into drugs—marijuana first and then cocaine. Eventually he started to smoke crack cocaine and, at that point, he was lost. He quickly began to rob the cash register to pay for his habit. And when his father died suddenly, the diner fell into disarray. After a couple of years, he had bled It dry to support his habit and eventually his mother’s home as well. For the next 10 years, Sakis would experience brief periods of sobriety. But he was never fully able to shake his demons and eventually was found dead from an overdose.

These stories, of course, are not unique. Go to any town where there is a Greek-American presence and you’ll unearth plenty of parallel experiences. The thread that binds them is an instinctual desire to keep things quiet and to handle

matters internally, most often within the insular family itself. But few are equipped for the task. To prevent tragedies like those of Stelios and Sakis, it’s important to seek professional help at the earliest signs of abuse. The fallacy that drug addiction doesn’t happen in good families will only delay the healing. And in sharing experiences, and being open about them, we may be able to help prevent some individuals from a horrible fate. To find help locally, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSA) operates a 24/7 national hotline and referral service at 1-800- 662-HELP (4357), where all information is confidential. SAMHSA is the agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that leads public health efforts to advance the behavioral health of the nation and to improve the lives of individuals living with mental and substance use disorders, and their families. They do not offer counseling services but route callers to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations. Callers can also order free publications and other information. The referral service is free of charge. Those without insurance and those who are underinsured are referred to the appropriate state office that is responsible for statefunded treatment programs. For more information, visit samsha.gov.

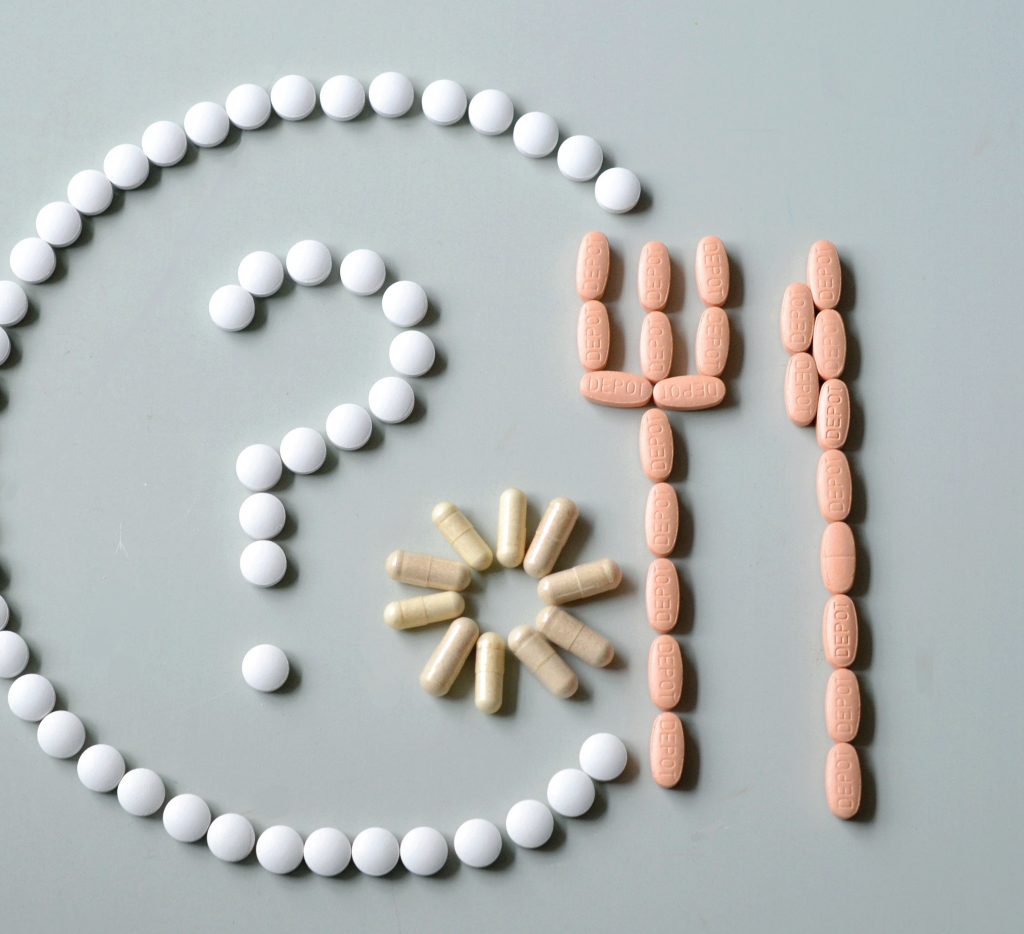

A VOCATIONAL HAZARD

11.8% of foodservice workers reported binge drinking during the last month

19.1% of foodservice workers report using illicit drugs during the last month

17% of foodservice workers have been diagnosed with substance use disorder

81% of survey participants responded that the drug they use most often is marijuana

31% of survey responded that the drugs they use most often are painkillers and prescription opiates

28% of survey responded that the drug they use most often is cocaine

8.3% of millennials indicate that they use drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

5.9% of Gen Xers indicate that they use drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

3.2% of baby boomers indicate that they use drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

10% of workers in the Midwest indicated that they used drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

7.2% of workers in the South indicated that they used drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

3.8% of workers in the Northeast indicated that they used drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

3.8% of workers in the West indicated that they used drugs on the majority of their foodservice shifts

20% of foodservice workers indicate that they use drugs and alcohol multiple times a week outside of work

40% of foodservice workers consider substance abuse to be a part of their work culture

30% of foodservice workers who were caught using illicit substances at work and reported no repercussions