Where Pizza Is Greek

Posted by estiator at 11 April, at 09 : 42 AM Print

A look into New England–style pan pizza and its origins.

By Constantine N. Kolitsas

I live in Connecticut, the self-proclaimed pizza capital of the United States. Known for its general New England snobbery, it’s no surprise, then, that the state is home to some of the most vociferous pizza snobs. Over the last decade or two, those snobs have controlled the narrative: insisting that great pizza must be Neapolitan-style thin crust, cook in a matter of minutes, and bake in brick ovens at temperatures exceeding 850 degrees. Three pizzerias in particular have entered into the lore of America’s culinary history: Frank Pepe’s, Sally’s Apizza, and Modern, all of which are known for coal-fired pizza that has put the city of New Haven on the culinary map. But the state’s dirty little secret is that Connecticut is just as famous for (and just as fond of) its Greek pizza—a very different and very delicious version that is thicker, baked in pans, and generally made with two types of cheese. And so, it’s time to flip the script and shine a light on the beloved pie that has been unfairly maligned.

To be up front, I own a pizza takeout business in Connecticut, having purchased it from the widow of one of the area’s early Greek pizzeria owners, the late John Kapetanopoulos. John and his former partner, Jimmy Sotiriou, along with a brother-in-law who sold his shares and moved back to Greece in the early years, opened Holiday Restaurant in New Milford, Connecticut, in 1963. And so, my exploration of Greek pizza is something of a journey of self-discovery, tapping into the history through the people who established it here in New England, and beyond.

“Greek pizza is a more complex pizza,” says Vasilis “Vasis” Kaloidis, scion of Toula and the late Athan Kaloidis, one of the state’s most well-known Greek pizza makers. “Most Italian pizzas have just three ingredients: flour, water and yeast.” The pizza he makes at the popular Spartan Pizza in Waterbury, Connecticut, he says, has six ingredients, including eggs. And the proofing process is very different. “We proof the dough three times,” he says. “After the first proof, we punch it down and let it rise again. Then we cut it and open it in the pan, where it proofs for a third time.” The result is a crust that is crispy, hearty, and flavorful.

“Greek pizza truly is a meal, where thin-crust Italian pizza is more of an appetizer,” says Peter Stefanopoulos, who, together with his brothers Billy, Chris, George, and Nick and brother-in-law Spiros Velezis, created the Four Brothers chain of pizzerias that run along the New York-Connecticut-Massachusetts borders. “Today, a family of four can come in and have a $20 pizza and be satisfied,” he says.

Chris Skarbandonis, the president of Connecticut’s Pan Gregorian restaurant cooperative, is the owner of Pizza Castle in Waterbury, a business his father has had since he was a teenager. “Our pizza travels very well,” he says, “where the thin-crust brick oven pizza turns to cardboard within ten minutes.”

“Greek pizza truly is a meal, where thin-crust Italian pizza is more of an appetizer,” says Peter Stefanopoulos

When I took over the Holiday Restaurant in 2020 and created Greca, an award-winning upscale Greek concept, I decided to hold on to the pizza part of the business, putting up a wall between the dining room and takeout area, and making the pizza takeout into its own brand, New Milford Pizza Station. At some point, I was debating whether to switch the pizza to a brick-oven-style pizza and ultimately decided to keep with the pan format (although I changed the dough recipe substantially, resulting in a much thinner crust, and removing the eggs). As Chris indicated, pan pizza is still delicious an hour after it’s been pulled from the oven. It may not still be piping hot, but it’s delicious. And a minute or two back in the oven to warm up and it’s perfect.

In reintroducing this pizza to the public, I wanted to distinguish it from the dozen or so other pizzerias in town, all of which offer some form of thin-crust New York–style pizza. I shied away from the term “Greek pizza” because I believed at the time that the Greek claim to pizza was just another example of us Greeks claiming another historical innovation. “New England–style pan pizza” is what I called it, adding “often referred to as Greek pizza for the Greek immigrants who developed the style here in the northeastern United States.”

But I was partially wrong, it turns out.

Dr. Dean Koutroumanis is a professor of management and entrepreneurship at the University of Tampa. In his scholarly article “The Missing Slice of the Pizza Pie: A Historical Look at the Origins of Greek Pizza,” he writes that the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all had a version of pizza. Known as “plankuntos” by ancient Greeks, a dough of flour and water was formed into round flat discs and baked on hot stones. The bread was used as an edible plate and topped with a wide variety of ingredients that might include stews or dates and spices. The fact that Naples, a Greek colony whose name is derived from the Greek words “Nea Polis (New City),” was an epicenter in the development of pizza offers another clue as to the Greek origin of pizza.

“Of course, putting tomato sauce on dough is something that happened much later,” says Stefanopoulos, pointing to the fact that tomatoes were indigenous to North America and brought to Europe after the trade routes were opened between the continents in the years following Columbus’s expeditions.

But as we talked, I became increasingly more interested in learning about the origins of Greek pizza here in the United States. In the ’60s and early ’70s, Greek pizzerias were popping up throughout the area, creating a new food phenomenon and making millionaires of the Greek immigrants who owned and operated them.

“I think that the first Greek pizza was made by a pair of guys from Epirus,” Stefanopoulos tells me. “They were working out of New Britain. That’s where most of the Greeks who opened pizzerias in the area learned how to make pizza,” he says. His own journey began in the early ’70s, in the quiet town of Lakeville, Connecticut. As time passed, he and his brothers listened to their neighbors across the New York State line and opened the first Four Brothers there. “We need your pizza here,” they were told. In the span of just a few years, they grew the Four Brothers footprint with new store after new store. Today, there are nine Four Brothers locations, which are being run by the next generation of Stefanopouloses.

“You know, that’s a good question,” laughs Skarbandonis, when pressed about the origins of Connecticut’s Greek pizza industry. “It probably began in the ’60s, but I don’t have any idea who it is that started it. My father, and many others, started in the ice cream business, driving trucks around the neighborhoods. Little by little, they all left that business and started pizzerias.”

Kaloidis also indicates that his father started driving ice cream trucks before he and his uncle George opened up their first pizzerias (incidentally, Vasi’s father sold Chris’s father his first pizzeria before opening Spartan Pizza in the mid ’70s). The late Spiros Velezis of Four Brothers and his wife, Lola, also had an ice cream truck. One of his routes took him into my neighborhood. At age seven or eight, I was one of his best customers.

As it seems, the Greek pizzeria owners are a fraternity of sorts, with most learning the business under similar circumstances. They are all good friends, even if they are rivals. But for all of this wonderful fraternization, I was only getting a little closer to the “creation” story of Greek pizza in Connecticut.

And then there’s another piece of the puzzle that took me into another direction: My father’s first cousins were making the same Greek pan pizza in Canada in the late ’60s. George, Tony, John, and Kostas Kolitsas made their way to Regina, Saskatchewan, in those years, and quickly opened a series of restaurants (Houston Pizza) that they eventually grew further by franchising to other Greek immigrants. At one point, they convinced my father to open a pizzeria here in Connecticut. But my father was a chef and felt creatively stifled in the pizza business. He sold after a year and went back to the business he loved.

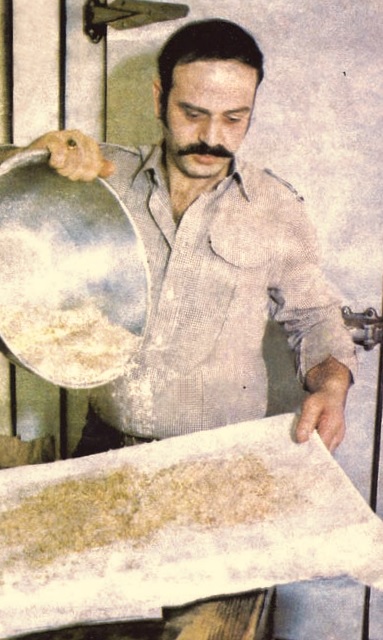

Finally, it’s in Dr. Koutroumanis’s research that the true story unravels. It turns out that the pan pizza made by the Greek pizzeria owners in Connecticut was first introduced in New London by two Greek immigrant bread makers, Charles Kay and James Diamond. It was in 1952 that the pair opened Pizza House in that coastal town, creating pizza from a recipe for lagana, “a type of peasant bread which has a crisp, flaky crust,” according to Koutroumanis. It was Kay and Diamond who also added a mix of white cheddar into the mozzarella, to give additional flavor to the pie.

In 1955, the partners opened a second location, Firehouse Pizza, in New Britain. And it was from this restaurant that the Greek pizza industry of New England was born. Apprentice after apprentice came through that restaurant, all Greek immigrants, with most soon opening their own pizzerias.

According to Koutroumanis’s research, one of those apprentices, Alex Zachary, opened Zachary’s Pizza House in 1957, after just six months working with Kay and Diamond. Soon after, he had grown into seven Pizza Pal units.

Another apprentice, George Zisopoulos, took what he had learned and taught it to several others, earning him the nickname “professor of Greek pizza.” In addition to teaching his “pupils” how to make Greek pizza, he schooled them in the economics and business aspects of running a successful pizzeria, going so far as to pointing them in the direction of college towns, which, he rightly indicated, were great markets for the product.

The pizza families who learned from Kay, Diamond, Zisopoulos, and others, are many, with several taking the phenomenon to other parts of the country. Among the most notable are the Fotopoulos brothers, who after opening ten pizzerias in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York made their way south to Florida, where they created the ABC Pizza House chain. It grew to 19 locations.

Whether Greek pizza is superior to the Neapolitan pizza that the pizza snobs hail is subjective. Personally, I dislike the coal-fired pizza of Frank Pepe and the New Haven pizzerias. The crust is charred and, to me, tastes like an ash tray. I also prefer the full flavors of the mozzarella and cheddar blend that characterize most Greek pizzas. I prefer the crust, and love that the toppings don’t all slide off the slice in an avalanche. And the sauce. Greek pizza sauce has a far more complex mixture of spices and herbs. But don’t let me (or the pizza snobs) tell you what is best. Taste for yourself and be the judge!