WWII: THE DECISION ON GREECE (Part II)

Posted by estiator at 15 February, at 13 : 10 PM Print

January-February 1941

The Italians driven back from Greece – Herr Hitler’s Balkan plans – We advance in the Western Desert – Herr Hitler’s orders for Sicily and Bulgaria – General Metaxas dies – A bad flight to Cairo with Sir John Dill – My “sealed orders” – Gen. Wavell favours a Greek campaign – He appoints General Wilson to the command – Athens – A moving interview with the Greek Prime Minister – Anglo-Greek decision to hold the Aliakhmon line-Prince Paul of Yugoslavia hesitates.

From the book The Memoirs of Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for War

(Previously published in the Greek-American Review, February 2004)

Hitler and Mussolini. Visit to Italy.

February 20th: Met three Commanders-in-Chief and Dill at Wavell’s office where we went into a three-hour session. There was agreement upon utmost help to Greece at earliest possible moment. There is grave risk in this course and much must depend on speed and secrecy with which it can be carried out. But to stand idly by and see Germany win a victory over Greece, probably a bloodless one at that, seems the worst of all courses. If we are to act we must do so quickly and we decided at a conference at Embassy later in the day that we would propose ourselves for a secret conference in Greece on Saturday.

Much discussion about Turkish position. [Gen. James] Marshall-Cornwall and [Air Vice-Marshal T. W.] Elmhirst [both of whom had recently been to Turkey as members of a mission for staff talks] gave doleful account of state of Turkish readiness. They do not know how to use technical arms and their operational efficiency in the air is very low. All this led Wavell to take the view, which Dill did not share, that Turks would be more a liability than an asset at present time.

February 21st: [Admiral] Cunningham put other point of view well when we discussed whole matter again this morning. “Would the Germans like best that Turks should stay out?”

Another full discussion this morning with C.-in-C’s found us all agreed on line with Greeks and our plans laid. Greeks have accepted visit.

After the meeting I sent the Prime Minister a telegram describing our interim conclusions:

Dill and I have exhaustively reviewed situation temporarily [5] with Commanders-in-Chief. Wavell is ready to make available three divisions, a Polish brigade and best part of an armoured division, together with a number of specialized troops such as anti-tank and anti-aircraft units.

Though some of these … have yet to be concentrated, work is already in hand and they can reach Greece as rapidly as provision of ships will allow. This programme fulfils the hopes expressed at Defense Committee that we could make available a force of three divisions and an armoured division. In order to do this we shall have to place a severe strain on administrative services and have to improvise widely. You can be sure that we are not being bound by establishments laid down. In fact, we could not possibly make available such a force in so short a time if we were.

Gravest anxiety is not in respect of army but of air. There is no doubt that need to fight a German air force, instead of Italian, is creating a new problem for Longmore. My own impression is that all his squadrons here are not quite up to standard of their counterpart at home. Having been very hardly worked in chasing Italians these last months, some of them are tired and … the supply of modern aircraft still leaves much to be desired. Many good troopers are still mounted on wretched ponies. We should all have liked to approach Greeks tomorrow with a suggestion that we should join with them in holding a line to defend Salonika, but both Longmore and Cunningham are convinced that our present air resources will not allow us to do this. Dill and I are not prepared to take a final decision until we have discussed the matter with the Greeks.

As regards general prospects of a Greek campaign, it is, of course, a gamble to send forces to the mainland of Europe to fight Germans at this time. No one can give a guarantee of success, but when we discussed this matter in London we were prepared to run the risk of failure, thinking it better to suffer with the Greeks than to make no attempt to help them. That is the conviction we all hold here. Moreover, though campaign is a daring venture, we are not without hope that it might succeed to the extent of halting the Germans before they overrun all Greece.

It has to be remembered that the stakes are big. If we fail to help the Greeks there is no hope of action by Yugoslavia, and the future of Turkey may easily be compromised. Though, therefore, none of us can guarantee that we may not have to play trump cards[6] we believe that this attempt to help Greece should be made. It is, of course, quite possible that when we see the Greeks tomorrow they may not wish us to come. If so, a new situation will have been created in respect which we will have to think afresh. But all my efforts will be concentrated on trying to induce Greeks to accept our help now.

We have discussed the question of command. Dill, Wavell and I are all agreed that we must select a figure who will command respect with the Greeks and exercise authority over the Greek officers with whom he will have to work. It is also necessary to choose a first-class tactical soldier. We have, therefore, decided that the command should be given to Wilson, who will be replaced in the military governorship of Cyrenaica by Neame, at present commanding in Palestine. … Wilson has a very high reputation here among the general public, as well as amongst the soldiers, and his appointment to lead the forces in Greece will be a guarantee to the Greeks that we are giving of our best.

That same night Dill sent the following message to General Haining, the V.C.I.G.S.:

I came out here with firm idea that forces sent to Greece would inevitably be lost and that we should concentrate on help to Turkey. I have now heard views of three Commanders-in-Chief, Marshall-Cornwall and Heywood [the army member of our Military Mission in Greece]. It has been made clear to me by them:

(a) That Turkey will not fight at our bidding.

(b) That she may fight if we show that by helping Greece we can stem a German advance.

(c) That there is a fair military chance of successfully holding a line in northern Greece if we act at once.

(d) That Yugoslavia will not fight unless Turkey fights and that the converse is very likely true.

I have concluded that our only chance of preventing the Balkans being devoured piecemeal is to go to Greece with all that we can find as soon as it can be done. The risks are admittedly considerable but inaction would in my view be fatal.

It is not yet possible to see what line we should aim at holding in Greece but I doubt very much whether Salonika could be covered. If this proves to be so after our discussion with Greeks tomorrow we may still be able to hold a line covering northern Greece and giving Yugoslavia a bolt-hole through the Monastir Gap.

The greatest risks are shortage of air forces and A.A. units, strain on administrative services, and fact that “Mandibles[7]“ cannot be completed until concentration in Greece is well under way or even finished.

Shipping needs can only be met by holding ships from convoys arriving here and further difficulty is mining in Suez Canal which is not yet fully under control. This makes it increasingly urgent to complete “Mandibles” and all energies are being directed to this end.

Line to take with Turkey is dependent on what Greeks reply to our proposals. Turkey as an ally would inevitably demand war material which we cannot supply and her forces are not really fit to meet Germans. Nevertheless I think we must try to persuade (but not bully) her to come in now as this will be her last chance. There are those who consider that Turkey in the war would be liability and would prefer to see her remain neutral.

Have had long talk with Donovan. He clearly thinks that help for Greece is urgent.

Though the force to be sent to Greece was a high proportion of the army’s total strength in the theatre, the percentage of armour to be called upon was relatively small, one brigade, and it was armour which was expected to play the decisive part in any revival of desert warfare.

***

February 22nd: Left aerodrome at 8 a.m. for Athens. Smooth and pleasant flight via Tobruk where we met Jumbo Wilson and made tour of Italian sheds and workshops while aeroplane refuelled. Islands and Greece itself looked lovely in the sunlight as we flew in. Motored with all discretion, Generals being disguised in civilian hats and overcoats, to Tatoi, the King’s country Palace. The King met us, and asked me for a talk alone when he told me of his troubles. He had worked hard to recreate his country since his return and now all was to be destroyed by German attack. He was determined to resist.

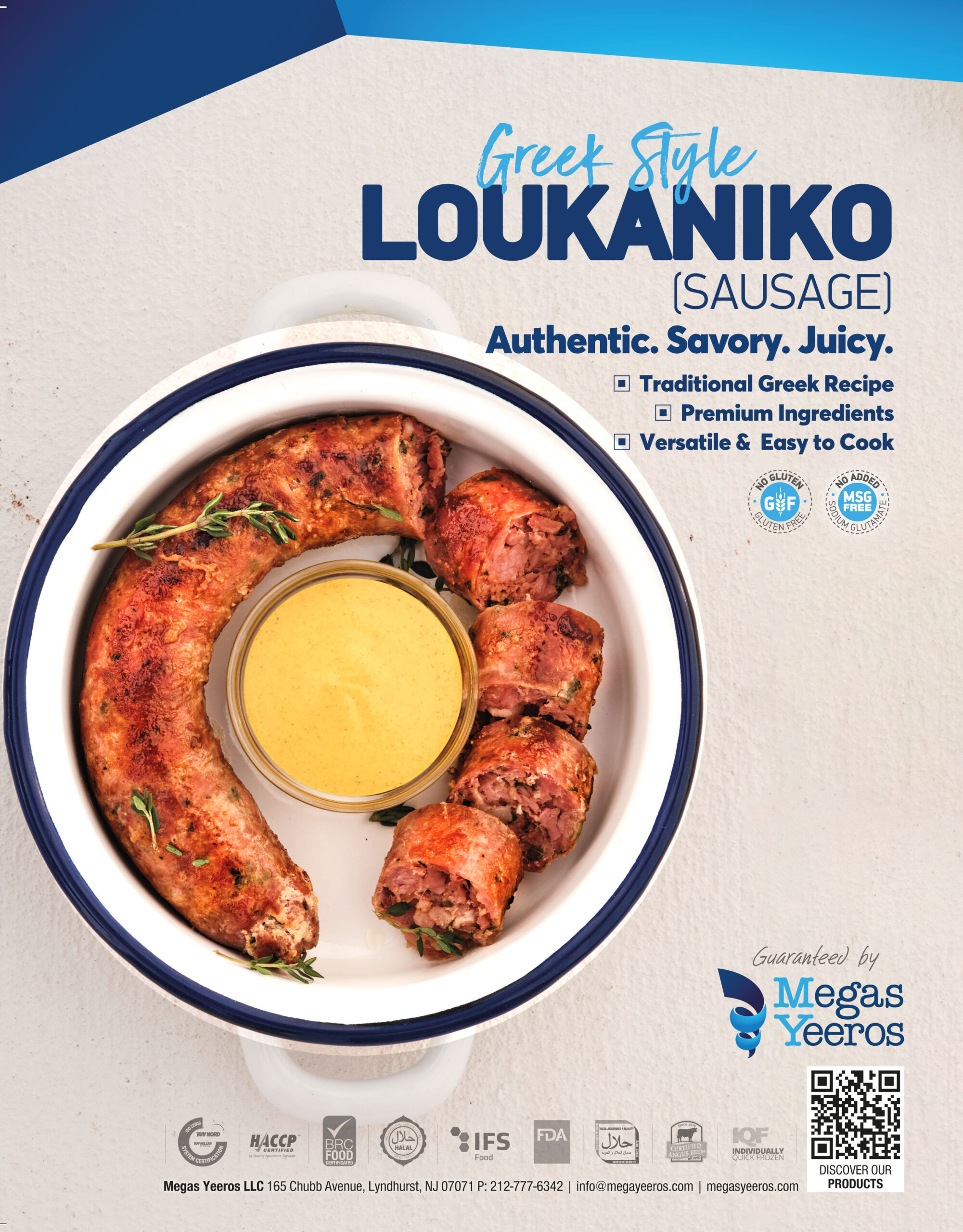

L: King George II – M: Churchill and Wavell – R: General Papagos.

King George of the Hellenes was resentful of some rumors which he had heard to the contrary. There was not a word of truth in any such suggestion. His Majesty then said that he wanted me to have a word with his Prime Minister, alone, before we got down to discussing plans. I told the King that as we had come on a military mission, to decide whether or not there was a military operation which we could carry through together, I was reluctant to begin with a political discussion with the Prime Minister. The King replied that he was not asking me to say anything, but that the Prime Minister had something he wanted to say to me. It would not take more than a few minutes. I could not refuse and we were thereupon put into a small anteroom together.

I can see the scene in my mind now. M. Koryzis produced a piece of paper which he read out in French and then handed to me. The declaration said that Greece, having given our spontaneous guarantee and having received our valuable help on the unprovoked aggression of Italy, was our faithful ally. She was determined to continue the struggle at our side until final victory. The resolve of the King and the Government, shared by the whole Greek people, applied no less to an attack by Germany than to the Struggle against Italy. The statement ended:

But let me repeat once again that whatever the future holds in store, and whether there is any hope of repelling the enemy in Macedonia or not, Greece will defend her national soil, even if she has to do so alone.

Looking back now upon the events of those days, I have no doubt that this modest little display of dauntless courage had been staged by the King. Irked by the rumours to which he had referred, he had been firm to explain his country’s true intent, before the British representatives could say a word. It was all of a piece with the sense of duty which invariably guided King George, with the result that he made no single mistake in these months of ordeal, where many a cleverer man would have tripped.

We then went in to the meeting, at which the chief Greek representatives were the King, M. Koryzis and General Papagos. Our side consisted of myself and Dill, Wavell, Longmore and a member of Cunningham’s staff, Heywood, Palairet and Pierson Dixon. I began by giving an account of the situation in the Balkans as it had appeared to the British Government in London the week before. The Germans had assembled a striking force in Roumania. We believed this to consist of twenty-three divisions of which three were armoured, supported by between four hundred and five hundred aircraft. The German infiltration into Bulgaria had gone far, technicians in plain clothes were busy establishing their air organization on Bulgarian aerodromes. If the reports just received were correct, the Germans were likely to cross the Danube at any moment. Their motives were to subdue Greece and immobilize Turkey. By extending their power over the Balkans, the Germans sought to strike a decisive blow at the British position in the Near East.

I explained that when the Greek Government had, on February 8th, appealed to the British Government for help and counsel, we had considered what we should do. Our Ministers, with the Chiefs of Staff in London and the three Commanders-in-Chief in Cairo, had agreed that we ought to offer all the help we could to Greece at the earliest possible moment. If action were to be taken, we must move with speed and in the utmost secrecy. I then gave details of the forces we could send, by land, sea and air.

M. Koryzis said that Greece was determined to defend herself against attack from all quarters; any aid which Great Britain could give her was warmly welcomed. He did, however, wish to draw our attention to the danger of precipitating a German attack. We should first consider whether the Greek forces and those that Great Britain could provide would be sufficient to give effective support to Greece, in view of the dubious attitude of Yugoslavia and Turkey. The Prime Minister emphasized that he raised this as a purely military and not as a political question. He also asked what we thought the attitude of Yugoslavia and Turkey was likely to be.

I told M. Koryzis that we did not know what those two countries would do. Sir John Dill and I were to visit Ankara and hoped to get an indication then. We should have to explain to the Turks that our help to Greece meant that we could not give Turkey the military aid she was expecting. We could hope Turkey would understand that Britain helped her best by helping Greece. I emphasized that it was important that we and the Greeks should take our decisions independently of the attitude of Turkey and Yugoslavia, since if we waited to find out what they would do, it might be too late to organize an effective resistance to a German attack on Greece. We then adjourned for the military to do their work.

At the military meeting General Papagos said that:

[he] realized the extreme importance of time, which made it impossible to wait for Yugoslavia and Turkey to declare themselves. He had therefore asked his Government for permission to begin the withdrawal [to the Aliakhmon line[8]] as soon as possible and, in any case, before a German move made the withdrawal look like a retreat. It could be made to appear that the Greek troops were being sent to reinforce the Albanian front. Troops would be withdrawn first from rear areas in Macedonia, then, if agreed with Turkey, from Thrace, and lastly from the frontier of Macedonia. The time required to withdraw the troops from Thrace and Macedonia was twenty days.

When the withdrawal was complete, the Greeks would have thirty-five battalions on the Aliakhmon line, plus one division, motorized, at Larissa, and possibly one more from reserve. It would then be possible to withdraw the right of the line in Albania.

There would then remain only frontier guards and light covering troops on the Bulgarian frontier. Those would fight to the last in all positions prepared for all-round defence; from other positions they would withdraw after delaying action. A plan had been prepared for demolitions in Eastern Macedonia, to be carried out by detachments of troops left for this purpose. A similar plan was under consideration for the Vardar valley ….

Children in Greece during WWII.

If Yugoslavia said tonight that she was going to fight, the Greeks would hold the Nestos line and ask the British to land at Salonika and Kavalla. Asked if the Greeks could cover disembarkation at Salonika, General Papagos said they would do their best: there were ten heavy and thirty-two light A.A. guns at Salonika. If the Aliakhmon line was held, these guns would remain at Salonika till the last phase of the withdrawal to the line…

The Germans would need twenty days, if the demolitions had been made, from the time of crossing the frontier before they could be ready to attack the Aliakhmon line in sufficient strength. The line was naturally strong and the thirty-five Greek battalions with the British forces offered should be able to hold it. There were no fortifications, but the field works constructed by the troops themselves should suffice.

When the British military representatives came to tell me the result of their discussion with the Greeks, we all agreed that unless we could be sure of the Yugoslavs joining in, it was not possible to contemplate holding a line covering Salonika. In view of the doubtful attitude of Yugoslavia, we considered that the only sound plan from the military point of view was to stand on the Aliakhmon line.

***

I dined with the King in a small party, including his brother and sister-in-law Prince and Princess Paul of Greece. The presentations were somewhat mumbled by the King, English fashion, and I was preoccupied by the discussions of this extraordinary day. After dinner there was some talk about German behaviour in the war and I made comments which, though no doubt critical, did not seem unduly so to me in the atmosphere of that time. As we left for the final meeting of the conference, the King said somewhat quizzically to me: “Rather severe on my sister-in-law, weren’t you?” I had to confess that, though struck by her beauty, I had not known who she was, which was not a good mark for my diplomacy.

At our final meeting to review our discussions, General Papagos himself began his report with the statement that in view of the dubious attitude of the Yugoslavs and Turks, it was not possible to contemplate holding a line covering Salonika, and that the only sound line in view of the circumstances was the line of the Aliakhmon.

The General followed this up by declaring the importance of the Yugoslav attitude, upon which depended the choice of the line to defend Greece. General Wavell, who spoke next, left no doubt that, in view of the time factor as well as the attitude of Yugoslavia and Turkey, the Aliakhmon line must be preferred. Later, after discussion about what could be done to enlist Yugoslav help, I asked that the decision be taken on whether preparations should at once be made, and put into execution, to withdraw the Greek advanced troops in Thrace and Macedonia to the line which we should be obliged to hold, if the Yugoslavs did not come in. Our minutes record that it was agreed that this should be done.

It never occurred to the British representatives either then or later that the Aliakhmon line was not the one which we must hold. A variant would only have been possible if the Yugoslavs had promptly declared their intention to enter the conflict, which we none of us expected, and if we and the Greeks had then had time to make detailed plans with them for the co-operation of our forces. When, years later, General Papagos wrote[9] that the decision on the line to be held in Greece was only intended to be taken after we discovered the Yugoslav intentions, Wavell and I discussed this apparent misunderstanding. We were both at a loss to comprehend how there could have been doubt in the mind of the Greek Commander-in-Chief.

His account spurred us to set down our own and we planned to write a book to which Wavell would contribute the military chapters and I the political. Unfortunately his death in 1950 put an end to this idea. Nothing survives except the Preface, which was his writing.[10]

At the end of the discussions at Tatoi, I said that we must be sure about one thing: did the Greek Government really welcome the arrival of British troops in the numbers and on the conditions proposed? We should have to set preparations in train immediately and we did not want anyone to think that we were forcing our help on the Greeks. M. Koryzis was visibly moved and said at once that the Greek Government accepted with deep gratitude the help we had offered and entirely agreed with the plan put forward by the military representatives. The War Cabinet in London later endorsed these proposals.

We also spoke with the Greeks about how I should deal with the Turkish Government when I visited Ankara in a few days’ time, and discussed how to get into touch with Prince Paul of Yugoslavia. It would have been too risky to send a staff officer to inform him of our decisions. Instead I instructed our Minister in Belgrade, Mr. Ronald Campbell, to tell Prince Paul that a German advance on Salonika seemed certain and that it was urgently necessary for us to know what Yugoslavia’s attitude would be. I also suggested that the Prince Regent should send M. Dragisa Cvetkovid or M. Alexander Cincar-Markovic1, the two Ministers who had just been to Germany, to meet me in Athens or Istanbul. During the next two months Campbell and his small staff in Belgrade had to live and work at high pressure in an atmosphere of mounting tension. They never faltered in advice or action and the Minister’s influence played a decisive part in shaping events.

When Prince Paul saw Campbell, he toyed once more with the idea of meeting me himself, but finally turned it down on the ground that it would cause “great trouble.” He told our Minister that he found it very difficult to answer my question about what Yugoslavia would do, without knowing what we intended to do. It would have been scarcely possible to tell him, even if I had been able to see him; nor would anything I could have said been likely to influence his decision. We now read that on February 24th his confidential emissary, Stakic, told Mussolini that the Prince had become convinced Britain could not win the war and that he must, therefore, make an agreement with Italy, which of course meant Germany, too.[11]

February 22nd: I authorized Wavell to set his plans in motion and Dill and I worked until 3 a.m. preparing messages for London. From first to last Greek attitude has been entirely resolute. They are determined to resist whoever attacks. Only doubt was whether to accept arrival of British troops now, or to await German attack and then call for them.

Our chief anxiety is in respect of the air. Longmore is much weaker than I had thought and much weaker than he should be. Flow of aircraft out to him has been recently most disappointing. It must be speeded up at all costs, and I only pray that the Hun gives us the time.

In any event our decision was the only one possible. On this I have no doubt.

FOOTNOTES

- Documents on German Foreign Policy; Series D, Vol. XI, Nos. 325-6, 328-q

- op. cit., No. 404.

- op. cit., No. 36g, Hitler’s letter to Mussolini, Nov. 20th, 1940.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1941; Vol. II.

- This word may have been wrongly decyphered.

- The text is obscure at this point, one group being undecypherable.

- A plan for capturing the Dodecanese, which was postponed because the transport of the force to Greece occupied all available shipping and naval re-sources.

- This line ran from the mouth of the Aliakhmon river through Veria and Edessa to the Yugoslav frontier.

- The Battle of Greece, 1940-1941.

- Printed as Appendix D.

- Documents on German Foreign Policy; Series D, Vol. XII, No. 85.